Frugality might have dictated a bus ride from the airport rental car drop-off to our hotel in the Santa Cruz barrio of Sevilla, but practicality, the pouring rain and Semana Santa, necessitated a taxi. The rain had canceled the Semana Santa processions that day, yet the streets which became increasingly narrow were clogged not only with the procession participants who had gathered instead at the home church (near our hotel), or maybe the ‘get out of the rain quickly’ church, but also with all the people who had come to stand watch. Our taxi driver could get no closer than 4 “blocks” from the hotel and let us out to brave the throngs. We felt like salmon swimming upstream against the current!

Later that evening, after we had enjoyed some authentic paella, we walked around near our hotel and discovered a huge crowd going in and out of a church. It was maybe the home church of one of the processions that had been canceled that day or the refuge church when the procession was caught in the rain. The pasos (floats) were on display and people were reaching out to touch them reverently and madly taking photos!

Only partially realizing what lay ahead, we returned to our hotel for some rest and the next day’s touring.

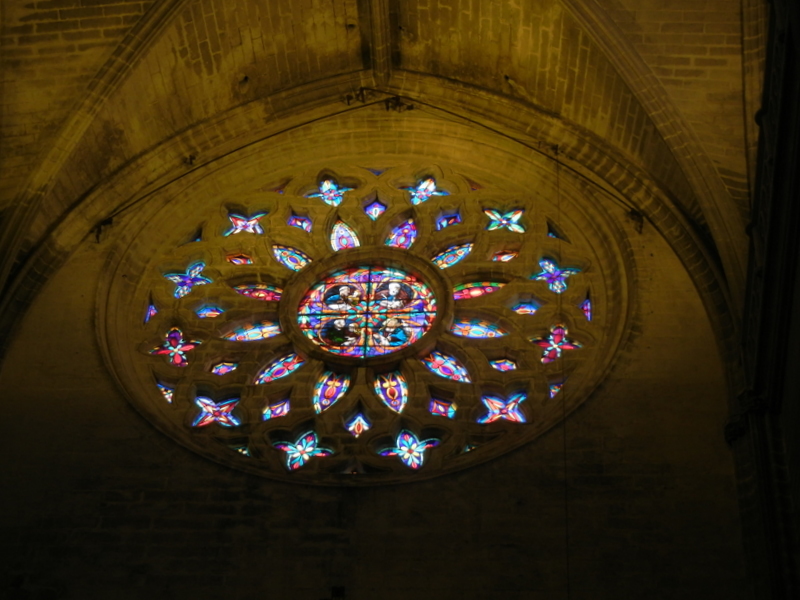

Seville’s cathedral is the biggest Gothic cathedral in the world, the third largest cathedral of any kind. As we now realize is somewhat the norm in Spain, it was first the site of the 12th century Almohad mosque (the Giralda minaret still stands), then a 15th century church. The church authorities decided to knock it down and start again, saying, according to legend, “Let us create such a building that future generations will take us for lunatics.” There was no way to get the entire cathedral into one photo frame, that is how huge it is!

Aside from its sheer size, the cathedral is notable for the tomb of Christopher Columbus, its beautiful carved high altar and its position as the mid-point of the passage for the Semana Santa processions. We found a door open, after our breakfast of croissant and freshly squeezed oranges, and went in; not much time to take photos as Mass was soon starting.

We sat down in the capille mayor for the Mass, which is also the only way to really see the high altar in all its glory. Still, I don’t take photos during worship so here is only a half view which I managed to capture after the Mass had ended and as the lights were being turned out!

Once we were ushered out after Mass, we were accosted by women pressing bunches of rosemary into our hands and telling our fortunes, then asking for money. There was also an enormous line waiting to get into the Cathedral.

These children had other things on their minds!

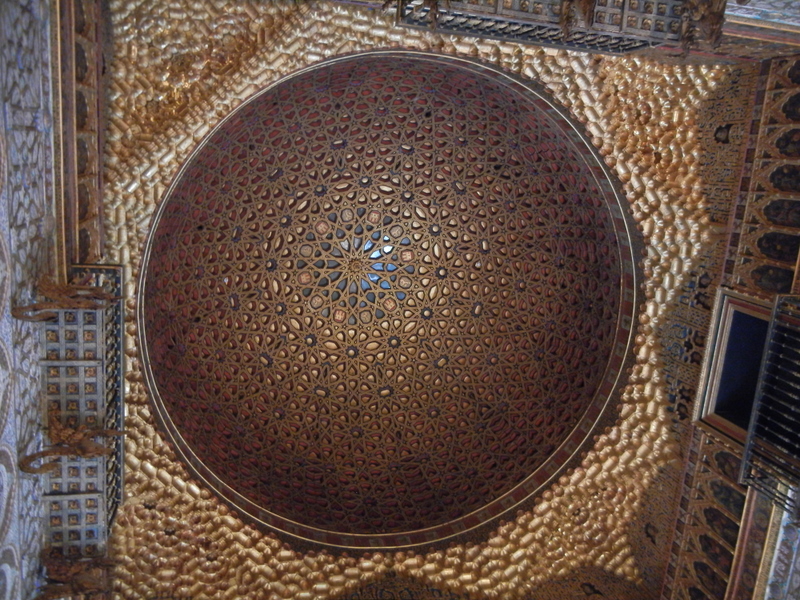

So we moved on to the Alcázar, (click link for history and description) and stood in the shorter line with some young men, students from, of all places, William and Mary College in Virginia (my home state) and Seattle! Alcázar was beautiful inside and out.

Great symmetry and great detail are the hallmark of the Moorish architecture. The kings of Spain who added on or remodeled followed suit. We hardly knew where to look next!

Water was an important feature in the culture.

Out in one of the many gardens, we got a little excited about a pair of parakeets making whoopee, not for that reason, but because we wondered if they were migrating through. We scrambled for the bird book and found alas, they are just another introduced or escaped species.

At that point it was time for a break, so with one last look at the beautiful architecture and plantings,

we threaded our way back through the twists and turns of the Barrio to rest. The Spanish definitely have the right idea about siesta! We’d rested only a little while, however, when we heard some noise and music in the street below our hotel room. Semana Santa!

For Christians in the US, Holy Week, the time between and including Palm Sunday and Easter, could be a focal point of the whole church year. Services are held on Palm Sunday, and then again in some parishes on Thursday, Friday, Saturday and culminate with Easter Sunday. More the norm is that the mid-week services are attended by some, but not nearly as well-attended as the services on Sundays. It is as if people move from Palm Sunday to Easter without traveling through (or thinking about) the passion and suffering.

What we were about to view on Wednesday afternoon and evening in Sevilla was nothing like we have ever seen. Truth be told, I am still processing the experience.

For, if you were from Spain, and especially Seville, (or Portugal, Latin or Central America, Italy, the Philippines–all locations where Holy Week is observed in a very public way) the Semana Santa or Holy Week would be filled with active participation in and fervent, public display of the Passion. No jumping from the palm-waving high of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem to the glory of the empty tomb.

Your brotherhood’s band, if there was one, would lead the way.

As part of a Roman Catholic Brotherhood (Hermandades y Cofradias de Penitencia) connected to a parish and as an act of penitence, you might be walking on one of those days in a procession, dressed in a long robe (different colors for different brotherhoods), cinched at the waist with a narrow cord or wide belt, wearing a pointed head piece with a cape attached (capirote) that allows only eyes to be seen, and carrying (in gloved hands) the largest candle imaginable or maybe a wooden cross or a staff.

You might be walking barefoot, in socks or in shoes or carrying a basket of candy or small photos of Mary or Jesus to give out to people along the route. You, as a Nazarenos, would walk as part of a double line of people, in groups of about 20 to 30 people, led by guardians who keep the formations organized by occasionally standing in the middle of the two lines and rapping the end of their staffs on the street.

You might be behind the leading band of drummers and trumpets/cornets (if your parish had such a band), or in front of similar bands and military guards

that sometimes follow the pasos (large floats bearing a lifelike wooden sculpture depicting an individual scene in the Passion of Jesus, or a weeping Mary, gently restrained in her grief.) These statues are venerated the rest of the year in your home church or at the home temple of the Brotherhood, and some are considered artistic masterpieces.

You might be a man or woman, a teenager or a child, as young as 3 and as old as, well, who knows?

You would walk mostly in silence – I never heard the Nazarenos speak a word to anyone watching along the route, and only occasionally to each other. (I did see a few people, especially children whose parents might have been on the support side lines, eat a bite, take a drink of water, or check their cell phone messages!) On early Friday of Holy Week, the Silencio brotherhood walks in absolute silence, not only within their own ranks but also among the spectators.

If you were amazingly strong, you might be one of the 24 to 40 men who have the honor of carrying the one-ton paso on their shoulders and necks, hidden from sight by a curtain, walking in complete unison with one another and with the drum corps or music. In that case you, as a costaleros, would be wearing a sleeveless shirt, trousers, a rolled up ‘sack’ on your head and neck, braces on your arms and knees, and sturdy cross-trainers. Every now and then, you would lower the paso altogether, and change places with a fresh group of costaleros. You would know what to do by listening to an outside overseer (capataz), who guides the team by voice, and/or through a ceremonial hammer el llamador (caller) attached to the paso.

The pasos of Jesus and Mary would be preceded by the priest and acolytes of the parish, and incense. At this point, the crowd would take on major proportions!

When the paso stopped, the band would play a song or someone from a balcony might sing a Saeta, a special devotional song without accompaniment, to Jesus or Mary. Then the crowd would be very still so as to hear every word. And at the end of the song, there would be much applause and cheering.

Children watching along the route would beg for candy during the day but at night their silent requests turned to drops of wax from the 1 meter candles, from which were constructed giant wax balls. Not one Nazarenos turned down such a request.

The streets would be so crowded, with spectators from all walks of life, hands reaching out to touch especially the paso of the bejeweled, canopied Virgin as she passed, a huge throng of mostly women dressed in street clothes following her.

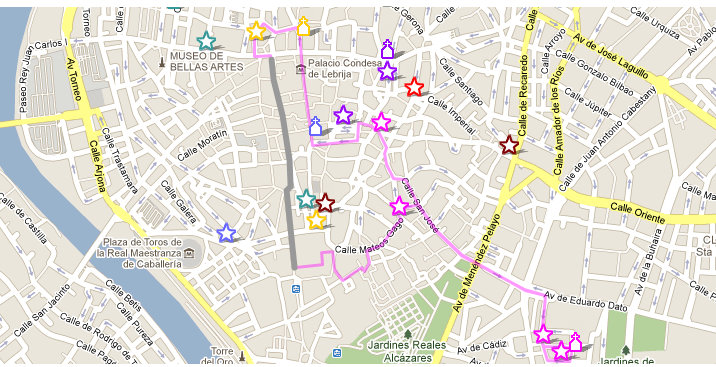

These processions, up to 6 a day in Sevilla, proceed from the home parishes to the Great Cathedral in Sevilla, process around the plaza in front of the Cathedral; enter the Cathedral and then process back home again to their parish. It’s even more impressive when you realize that some of these parishes are outside of Sevilla a-ways, such that people are walking for 14 hours. The routes and timetable are predetermined and adhered to religiously.

If it rains, the processions are canceled, rather than risk damage to some of the pasos. Which was why they were in the building the night before.

The procession we watched on Wednesday of Holy Week, one of the few days in Sevilla without rain, began at the home parish of San Benardo (which wasn’t all that far from the cathedral as the crow flies), a parish/brotherhood with some historic association to bull fighters and which dates from around 1748. The 2400 Nazarenos of the Brotherhood (men, women children), journeying with the pasos of the 1669 Cristo de la Salud and the 1938 Maria Santisima del Refugio, began at 2 PM in the afternoon and didn’t finish until at least midnight that same day. They walked and carried the candle and flower-bedecked pasos up and across the Puente de San Bernardo (San Bernardo Bridge), wound their way through the streets of the Barrio de la Santa Cruz, to the Cathedral and then back again. They passed our hotel for about two hours, in the mid to late afternoon and returned again late at night.

For mainline Protestants, all this spectacle is perhaps a little foreign. Better just to receive it than try to analyze. It is hard to describe in words the sense of devotion and passion that the procession conveyed. Here are links to a few videos that might bring it in closer for you.

Click on the photos to bring up the videos. The music played for the Jesus paso is more subdued than that for the Mary paso.

|

| From Spain 2011 – movies |

|

| From Spain 2011 – movies |

|

| From Spain 2011 – movies |

|

| From Spain 2011 – movies |

We wandered around much of the old quarter of Sevilla, taking in the smell of tapas, the color of the polka-dotted flamenco dresses, the shimmer of the fans, but nothing, nothing, compared to watching La Procesión del miércoles (Wednesday’s procession) which passed directly under our balcony in the late afternoon and returned again, candles lit, much later that evening. If it had been allowed, I might have sung a saeta, so moving was this demonstration of fervent faith.

Adios de España y vaya con Dios!